Did you know that the human heart beats about 100,000 times per day?! That means that during an average lifetime, a person’s heart beats more than 2.6 billion times (1)! Your heart rate, or pulse, is the number of times your heart beats per minute. It can vary from person to person based on factors such as hydration status, activity level, age, sex, overall health, medications, illness, sleep patterns, and stress (2, 3).

The Benefits of Heart Rate Monitoring for Health and Fitness

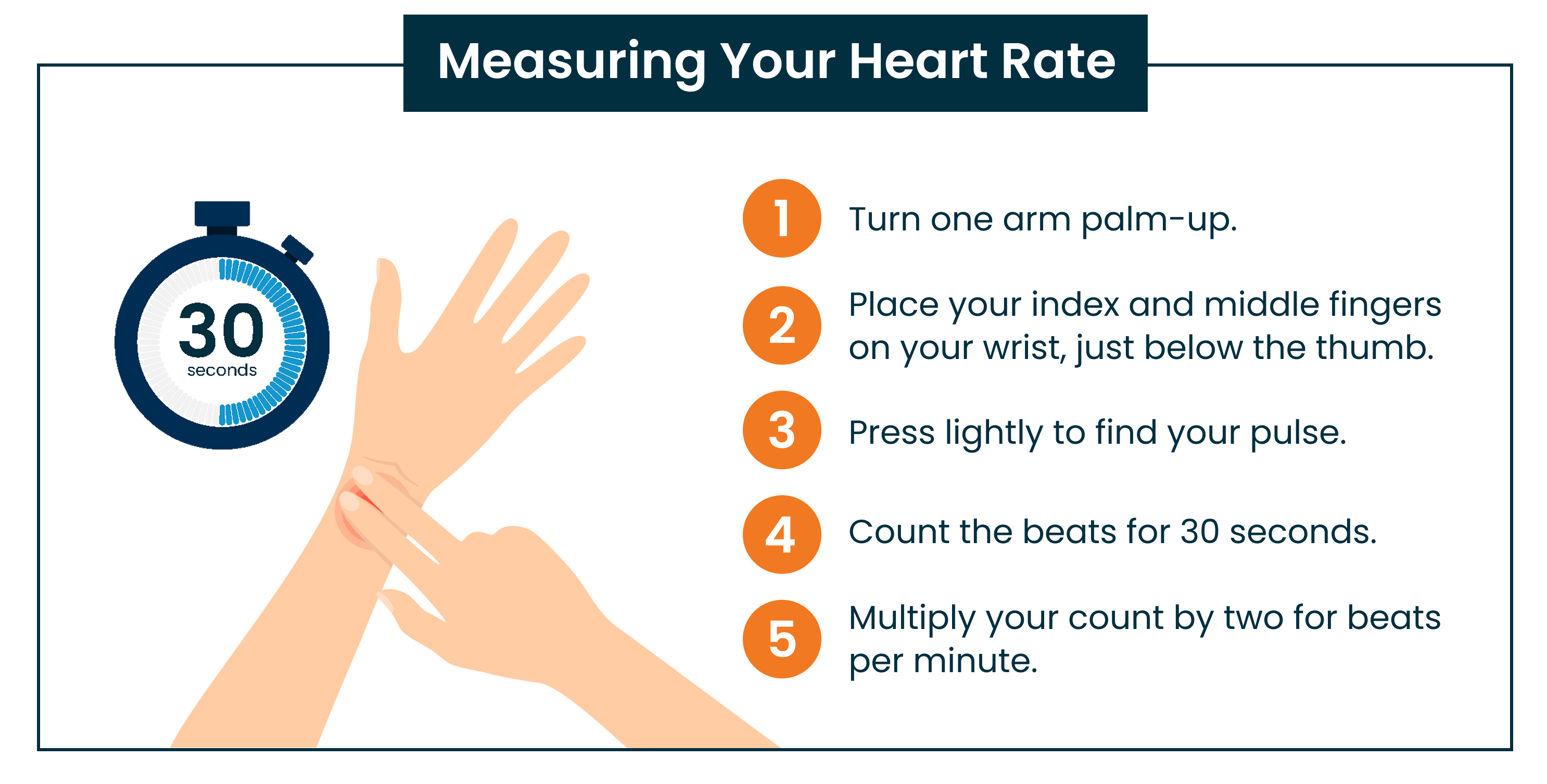

Heart rate monitors have become a common tool available in various forms, from sports bands to health-tracking rings. Whether you use these devices or not, knowing your baseline heart rate can be beneficial and provide valuable insights into your health and fitness level. If you don’t have a device to monitor your heart rate, use the five steps below to check it manually.

Whether you are at rest or in the middle of an intense workout, your heart rate can indicate your risk of heart attack and your aerobic capacity—the maximum amount of oxygen your body can utilize during exercise (3). Consistently monitoring your heart rate allows you to make informed decisions tailored to your fitness routine, helping you improve your health and achieve your fitness goals.

Measurements of Heart Health

Not everything in health can be measured, but tracking the right indicators allows us to manage and improve them effectively. Monitoring health metrics can help you measure progress, evaluate success, and make informed decisions. Here, we will discuss your Resting Heart Rate (RHR), Maximum Heart Rate (MHR), and Heart Rate Variability (HRV). These baselines offer valuable insights into your current fitness level and help guide safe and effective exercise practices.

“What gets measured gets managed”

Resting Heart Rate (RHR): Resting heart rate is the number of times your heart beats per minute when you are not active, such as when sitting or lying down. For most adults, a normal RHR is between 60-100 beats per minute (bpm). If you exercise regularly and maintain a healthy lifestyle, your resting heart rate might be lower. Think of it like a car engine: a strong, efficient engine runs slower but can perform more work. A lower resting heart rate is generally a sign of good fitness (5). However, several factors can influence this number, such as stress, anxiety, or certain medications (5). If you’re curious about your resting heart rate, consult your doctor. They can tell you what’s normal for you and provide tips for maintaining a healthy heart.

Max Heart Rate (MHR): Your maximum heart rate is the fastest your heart can beat during intense exercise. To estimate your max heart rate, use the formula:

For instance, if you’re 15 years old, your max heart rate would be 220 – 15 = 205 beats per minute. While you can’t increase your max heart rate, you can train your body to perform better when your heart rate is elevated. Understanding your max heart rate can help you determine how hard to work during exercise.

Heart Rate Variability (HRV): HRV refers to the variation in time between each heartbeat, measured in milliseconds. While heart rate is calculated as beats per minute, HRV focuses on the slight changes in time between consecutive beats. HRV is regulated by the autonomic nervous system, which controls involuntary functions like heart rate, digestion, and breathing. A higher HRV indicates that your body can adapt well to different situations, reflecting good health. In contrast, a low HRV suggests your body is working harder to maintain balance (7).

Several factors can temporarily lower HRV, including depression, stress, poor sleep, illness, dehydration, elevated body weight, or nutritional deficiencies (11-14). Low HRV is linked to various health issues, such as cardiovascular problems, chronic stress, inflammation, chronic fatigue, and mental health conditions.

To improve HRV, consider lifestyle changes like regular exercise, better sleep habits, stress management, a diet rich in omega-3 fatty acids, and reducing alcohol or stimulant consumption. These actions can enhance this critical biomarker of your overall well-being. HRV can also serve as a tool to guide daily decisions toward better long-term health (11-16).

Heart Rate Zones

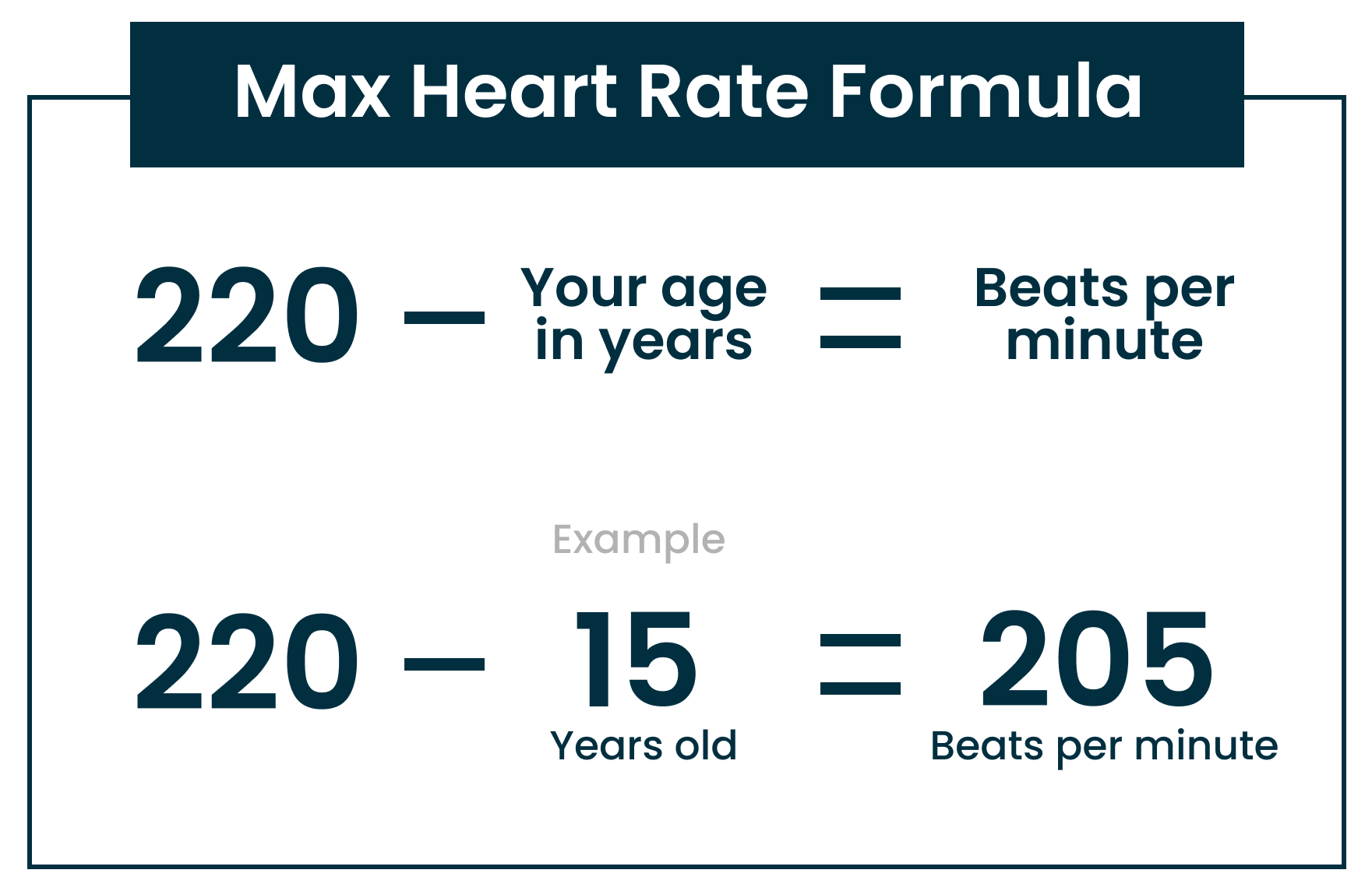

Your target heart rate zone is the range of heartbeats per minute that helps you achieve a specific workout effect (8). Heart rate zones allow you to evaluate the intensity of your exercise and align it with your fitness goals. Exercising within these zones can improve cardiovascular health, burn fat, enhance endurance, and boost insulin sensitivity (2).

Using your maximum heart rate (MHR) as a reference, you can calculate target zones as percentages of your MHR—a method known as zone training. In zone training, each zone corresponds to a percentage of the maximum number of beats your heart can produce per minute (8).

You can determine your current zone using a heart rate monitor or by applying the “talk test,” which assesses your ability to hold a conversation during exercise. For example, being in a lower zone means you can talk easily, while higher zones make speaking more challenging.

As you read about these zones and their effects, consider your usual exercise routines or movements. Reflecting on how your body responds can help you tailor your activities to better align with your fitness objectives.

Heart Rate Zones and Their Benefits:

- Zone 1 (50-60% of Max HR):

This is a low-intensity zone, ideal for warm-ups, cool-downs, and restorative training (8). Though gentle, it plays a vital role in building basic fitness, especially if you’re new to exercise or resuming after a break. It helps improve endurance and recovery. Activities in this zone often include walking, climbing stairs, stretching, light yoga, and slow walking. A good indicator is your ability to hold a conversation easily without losing breath. - Zone 2 (60-70% of Max HR):

Known as the fat-burning zone, this range includes light to moderate intensity exercise (8). While it may feel relatively easy, it effectively utilizes fat stores for energy during longer workouts. This zone is foundational for building fitness and endurance. You should be able to carry on a light conversation, though you may occasionally pause to catch your breath. Common activities include brisk walking, relaxed cycling, and swimming at a steady pace. - Zone 3 (70-80% of Max HR):

This moderate-to-vigorous intensity zone is where exercise starts to feel challenging and demands more energy from fats, carbohydrates, and proteins. It improves your ability to move efficiently and at speed (8). Talking becomes noticeably harder in this zone, making conversations less enjoyable. Activities include jogging, moderate cycling, and group fitness classes. - Zone 4 (80-90% of Max HR):

This vigorous-intensity zone is excellent for high-intensity training and performance improvement. Workouts in this range may involve both intervals (short bursts of effort) and steady-state efforts (8). Carbohydrates and proteins are the primary energy sources in this zone, rather than fat (8, 9). Speaking becomes uncomfortable, and you may only manage a few words if necessary. Examples include stair climbing, HIIT (High-Intensity Interval Training), and tempo training. - Zone 5 (90-100% of Max HR):

This maximum-effort zone is reserved for short, high-intensity intervals to enhance peak performance. Training here is challenging due to lactic acid buildup, often forcing you to stop after a few minutes (8). Talking is nearly impossible in this zone. Activities include maximum-effort sprints, cycling, swimming, Tabata training (20 seconds of effort followed by 10 seconds of rest), competitive sports bursts (like sprinting to score in basketball), and explosive plyometric exercises such as box jumps or battle ropes.

Understanding these zones can help you tailor your workouts to meet specific goals, from building endurance to maximizing performance.

Heart Rate Exercise

The American Diabetes Association (ADA) recommends getting at least 150 minutes (about 5 hours) of moderate to vigorous exercise per week. Reaching this goal might be easier than you think! You can break it down into manageable sessions, like 25 minutes a day for 6 days or 30 minutes a day for 5 days. Plus, you don’t have to do it all at once. For example, you could try three 10-minute walks after meals, which can be a great way to meet your exercise goals without feeling overwhelmed (4).

Both aerobic and resistance training exercises have been shown to reduce average glucose concentrations by approximately 10% (5). To maximize glucose control benefits, aim not to go more than 48 hours (about 2 days) between exercise sessions. A well-rounded routine might include 3 days of aerobic exercise, 3 days of resistance training, and a rest day each week. Consistency is key, and it’s important to avoid more than two consecutive days without some form of exercise (5).

While higher heart rate zones might seem more effective, workouts in lower heart rate zones are equally valuable and can still contribute significantly to your health goals. Regularly checking your Heart Rate Variability (HRV) can help you fine-tune exercise intensity and recovery periods, ensuring you’re exercising effectively without overexerting yourself.

Note: Always consult with your healthcare provider before starting a new exercise program.

The Importance of Consistency in Your Exercise Routine

When it comes to exercise, one factor outweighs all others in importance: consistency.

Consistency in an exercise routine is not just about sticking to a schedule; it’s about forming habits that lead to lasting health benefits. When you regularly engage in physical activity, your body begins to expect and enjoy the routine, making it easier to maintain over time. This enhances not only your physical health but also your mental well-being.

Imagine starting your day with a brisk walk or ending it with a calming yoga session. These consistent practices can become the highlights of your day, offering a sense of accomplishment and peace. Over time, the benefits compound—improving cardiovascular fitness, aiding in weight control, and significantly benefiting glucose regulation and overall health (5).

For individuals managing diabetes or at risk of developing it, consistent exercise is especially powerful. Regular physical activity improves insulin sensitivity, enabling your body to use insulin more effectively (10). This is particularly beneficial for those with insulin resistance or type 2 diabetes, as it helps lower blood sugar levels and maintain stability.

Beyond glucose control, the advantages of maintaining a regular exercise routine extend to mental health, stress reduction, and mood enhancement. The rhythmic nature of physical activity supports heart health by maintaining healthy blood pressure and cholesterol levels, reducing the risk of heart disease.

Remember: The key to success is consistency. Make exercise a regular part of your life, and the benefits—both physical and mental—will follow.

Sending Health Your Way!

The Tula Clinical Team

Reviewed by:

Aubree RN, BSN

Austin MS, RDN, CSR, LDN, CD

Spencer BS, CPT

Tula Takeaways |

|---|

| 1. Talk Test: Try the “talk test” during one of your exercises this week. See how easy or difficult it is to talk while exercising. Then, compare your experience to the heart rate zone chart above to get an idea of which zone you may be in. |

| 2. Make it Social: Consistency with habits doesn’t rely solely on strong willpower. Social support, enjoyment, and relevance also play significant roles in maintaining habits. Consider ways to make your desired habit more social, enjoyable, or relevant to your current life. |

| 3. Teach Someone: Sharing knowledge is a great way to solidify what you’ve learned. Challenge yourself to take one piece of information from this blog that you found insightful and share it with someone else! |

The LIVE TULA blog is informational and not medical advice. Always consult your doctor for health concerns. LIVE TULA doesn’t endorse specific tests, products, or procedures. Use the information at your own risk and check the last update date. Consult your healthcare provider for personalized advice.